In Face of COVID Threat, More Dialysis Patients Bring Treatment Home

NIPOMO, Calif. — After Maria Duenas was diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes about a decade ago, she managed the disease with diet and medication.

But Duenas’ kidneys started to fail just as the novel coronavirus established its lethal foothold in the U.S.

On March 19, three days after Duenas, 60, was rushed to the emergency room with dangerously high blood pressure and blood sugar, Gov. Gavin Newsom implemented the nation’s first statewide stay-at-home order.

Less than one week later, Duenas was hooked up to a dialysis machine in the Century City neighborhood of Los Angeles, 160 miles from her Central Coast home, where tubes, pumps and tiny filters cleansed her blood of waste for 3½ hours, doing the work her kidneys could no longer do.

In the beginning, Duenas said she didn’t understand the severity of COVID-19, or her increased vulnerability to it. “It’s not going to happen to me,” she thought. “We’re in a small little town.”

But she was unable to find a spot in a dialysis clinic in, or near, Nipomo. So, with her husband, Jose, at her side, Duenas made long road trips to Century City for more than two months.

In May, Duenas’ doctor told her she was a good candidate for home dialysis, which would save her drive time and stress — and reduce her exposure to the virus.

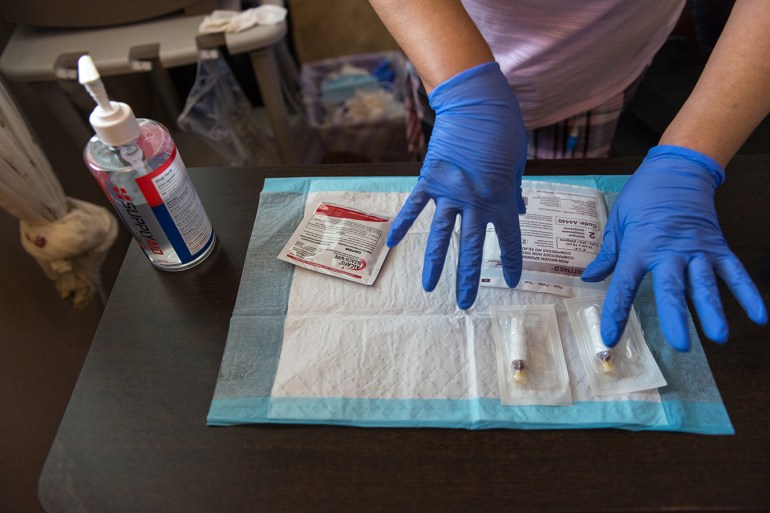

The closet in Duenas’ grandchildren’s playroom is crammed with peritoneal dialysis solution, a mixture of dextrose, calcium and magnesium. She uses two bags for every treatment. Cabinets and drawers in her bedroom are filled with disinfectant wipes, gauze, masks and gloves.

Now, Duenas assiduously sterilizes herself and her surroundings five nights a week so she can administer dialysis to herself at home while she sleeps.

“There’s always a chance going in that somebody’s going to have COVID and still need dialysis” in a clinic, Duenas said. “I’m very grateful to have this option.”

The increase in home dialysis has accelerated recently, spurred by social-distancing requirements, increased use of telehealth and remote monitoring technologies — and fear of the virus.

Duenas starts her home dialysis routine around 8 p.m. She must maintain a sterile environment and uses masks and gloves. Her husband, Jose, installed an automatic paper towel dispenser in their bathroom to help ensure proper hygiene.

While recent, comprehensive data is hard to come by, experts confirm the trend based on what they’re seeing in their own practices. Fresenius Medical Care North America, one of the country’s two dominant dialysis providers, said it conducted 25% more home dialysis training sessions in the first quarter of 2020 than in the same period last year, according to Renal & Urology News.

“People recognized it would be better if they did it at home,” said Dr. Susan Quaggin, president-elect of the American Society of Nephrology. “And certainly from a health provider’s perspective, we feel it’s a great option.”

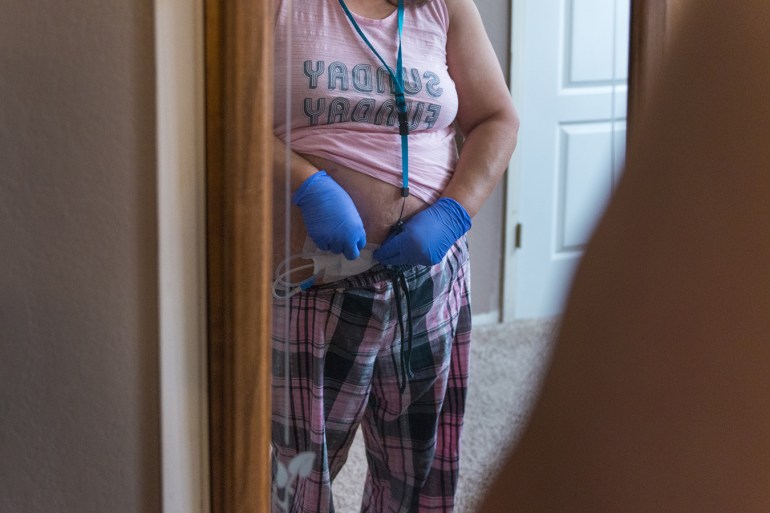

Duenas vigorously washes her hands before she cleans the area around the catheter in her abdomen. She also sterilizes the dialysis equipment before hooking herself up for the night.

Nearly half a million people in the United States are on dialysis, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Roughly 85% of them travel to a clinic for their treatments.

Dialysis patients are at higher risk of contracting COVID-19 and getting seriously ill with it, said Dr. Anjay Rastogi, director of the UCLA CORE Kidney Program, where Duenas is a patient.

In an analysis of more than 10,000 deaths in 15 states and New York City, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found about 40% of people killed by COVID-19 had diabetes. That percentage rose to half among people under 65.

But people on dialysis are also vulnerable to COVID-19 because they usually visit dialysis clinics two to three times a week for an average of four hours at a time, exposing themselves to other patients and, potentially, the virus, Rastogi said.

“Now even more so, we are strongly urging our patients to consider home dialysis,” he said.

Although patients on home dialysis reduce their exposure to COVID-19 by avoiding clinics, they face other challenges. Home dialysis requires supplies such as dialysis fluid, drain bags, tubing, disinfectant and personal protective equipment. According to a recent study, patients may have problems obtaining dialysis supplies because supply chains are strained.(Heidi de Marco/KHN)

Duenas uses her bedroom mirror to make sure her catheter is properly covered with gauze before she goes to bed. She will be tethered to the machine overnight.(Heidi de Marco/KHN)

There are two kinds of dialysis: hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. In hemodialysis, which is administered in a hospital or clinic, or sometimes at home, a dialysis machine pumps blood out of the body and through a special filter called a dialyzer, which clears waste and extra fluid from the blood before it is returned to the body.

Dialysis treatment centers that offer hemodialysis have intensified their infection-control procedures in response to COVID-19, said Dr. Kevin Stiles, a nephrologist at Kaiser Permanente in Bakersfield. Visitors are no longer allowed to accompany patients, and patients get temperature checks and must wear masks during treatment, he said. (KHN, which produces California Healthline, is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.)

In peritoneal dialysis, which is the more popular home option because it is less cumbersome and restrictive, the inside lining of the stomach acts as a natural filter. Dialysis solution cleanses waste from the body as it is washed into and out of the stomach through a catheter in the abdomen.

It takes Duenas about 45 minutes to prepare her overnight treatment. Her tubing allows her to get as far as her bathroom, but she sometimes gets tangled in it at night.

Not everyone is eligible for home dialysis, which comes with its own challenges.

Home dialysis requires patients or their caregivers to lift bags of dialysis solution that weigh 5 to 10 pounds, Stiles said. Good eyesight and hand dexterity are also critical because patients must be able to maintain sterile environments.

Home patients need dialysis equipment and regular deliveries of supplies such as dialysis fluid, drain bags, tubing, disinfectant and personal protective equipment. In response to COVID-19, some clinics have arranged courier services and contracted with labs to deliver supplies to patients.

The Trump administration has encouraged greater use of home dialysis and in July proposed increasing Medicare reimbursement rates for home dialysis machines, citing “the importance that this population stay at home during the public health emergency to reduce risk of exposure to the virus.”

The morning after her treatment, Duenas disinfects the dialysis machine and then disconnects her catheter tube from the machine so that she can move around freely.

Medicare covers almost all patients who receive dialysis treatment, including home dialysis, and patients typically pay 20% as coinsurance.

Medicare, which spends an average of $90,000 per hemodialysis patient annually, spent more than $35 billion on patients with end-stage renal disease in 2016.

Duenas is awaiting a kidney transplant. Until she finds a match, she’ll be administering her own peritoneal dialysis at home.

Duenas inspects her drain bag in the morning for fibrin, a protein that can clog her catheter. She must alert her doctor if she finds any floating in the fluid.

“To be honest, I didn’t want to do it,” she said of home dialysis. “It was scary having to think about taking care of my own treatment.”

Now, three months later, guided by training and the prompts on the dialysis machine, Duenas feels comfortable, capable and safe.

Looking back, she said, “it was a blessing in disguise.”