The twinkle in his eyes, the delight in his smile, the joyous way he moved his disease-withered frame. They all proclaimed a single, resounding message: Grateful to be alive!

“As my care team and my family tell me, ‘You were born again. You have to learn to live again,’” said Vicente Perez Castro. “I went through a very difficult time.”

Hell and back is more like it.

Perez, a 57-year-old cook from Long Beach, California, could barely breathe when he was admitted on June 5 to Los Angeles County’s Harbor-UCLA Medical Center. He tested positive for covid-19 and spent three months in the intensive care unit, almost all of it hooked up to a ventilator with a tube down his throat. A different tube conducted nutrients into his stomach.

At a certain point, the doctors told his family that he wasn’t going to make it and that they should consider disconnecting the lifesaving equipment. But his 26-year-old daughter, Janeth Honorato Perez, one of three children, said no.

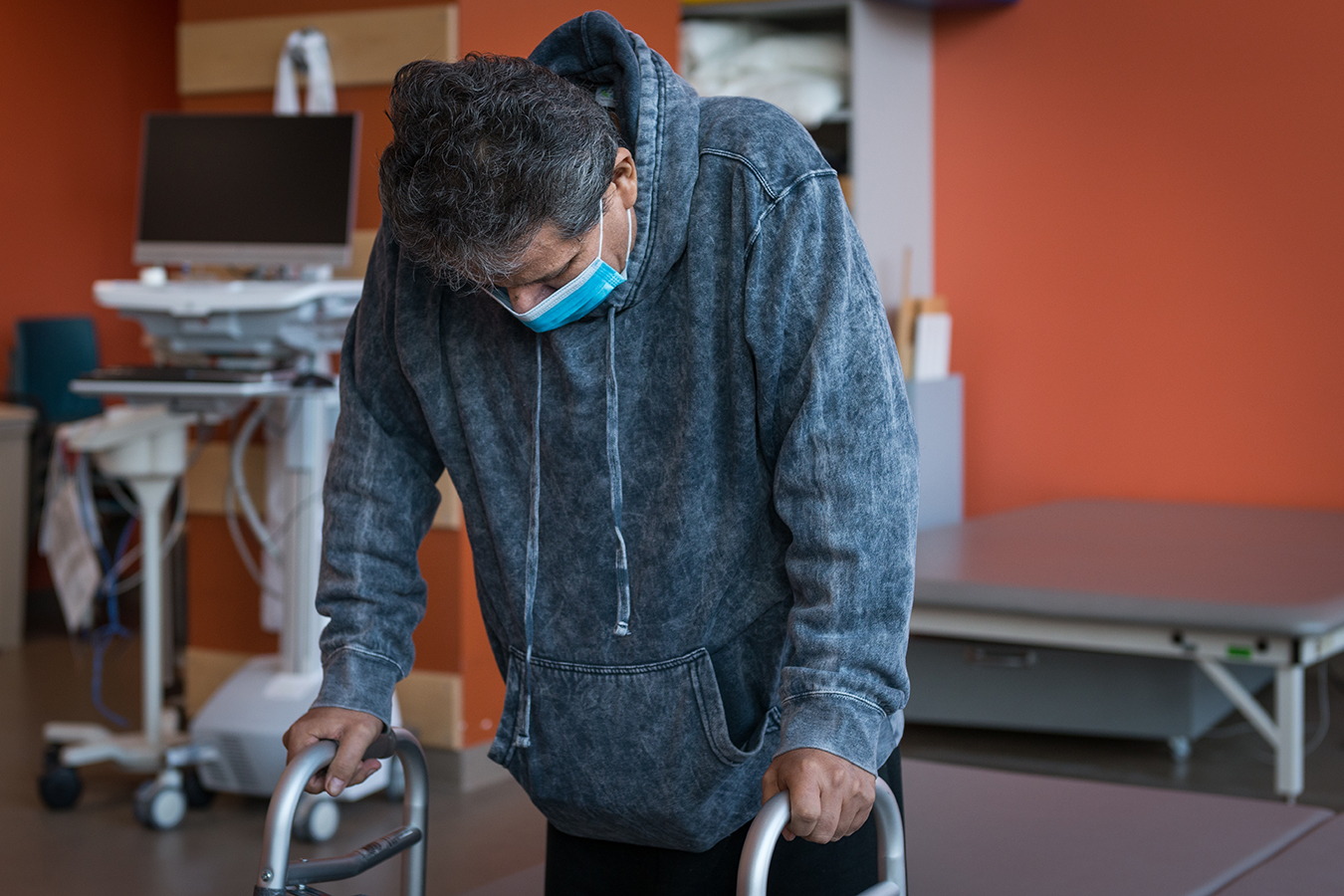

And so, on a bright February morning half a year later, here he was — an outpatient, slowly making his way on a walker around the perimeter of a high-ceilinged room at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Downey, one of L.A. County’s four public hospitals and the only one whose main mission is patient rehab.

Perez, who is 5-foot-5, had lost 72 pounds since falling ill. His legs were unsteady, his breathing labored, as he plodded forward. But he kept moving for five or six minutes, “a huge improvement” from late last year, when he could walk only for 60 seconds, said Bradley Tirador, one of his physical therapists.

Rancho Los Amigos has an interdisciplinary team of physicians, therapists and speech pathologists who provide medical and mental health care, as well as physical, occupational and recreational therapy. It serves a population that has been disproportionately affected by the pandemic: 70% of its patients are Latino, as are 90% of its covid patients. Nearly everyone is either uninsured or on Medi-Cal, the government-run insurance program for people with low incomes.

Rancho is one of a growing number of medical centers across the country with a program specifically designed for patients suffering the symptoms that come in the wake of covid. Mount Sinai Health System’s Center for Post-Covid Care in New York City, which opened last May, was one of the first. Yale University, the University of Pennsylvania, UC Davis Health and, more recently, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles are among the health systems with similar offerings.

Rancho Los Amigos treats only patients recovering from severe illness and long stays in intensive care. Many of the other post-covid centers also tend to those who had milder cases of covid, were not hospitalized and later experienced a multitude of diffuse, hard-to-diagnose but disabling symptoms — sometimes described as “long covid.”

The most common symptoms include fatigue, muscle aches, shortness of breath, insomnia, memory problems, anxiety and heart palpitations. Many health care providers say these symptoms are just as common, perhaps more so, among patients who had only moderate covid.

A survey conducted by members of the Body Politic Covid-19 Support Group showed that, among patients who’d experienced mild to moderate covid, 91% still had some of those symptoms an average of 40 days after their initial recovery.

Other studies estimate that about 10% of covid patients will develop some of these prolonged symptoms. With more than 28 million confirmed cases in the U.S. and counting, this post-covid syndrome is a rapidly escalating concern.

“What we can say is that 2 [million] to 3 million Americans at a minimum are going to require long-term rehabilitation as a result of what has happened to this day, and we are just at the beginning of that,” said David Putrino, director of rehabilitation innovation at Mount Sinai Health.

Health care professionals seem guardedly optimistic that most of these patients will fully recover. They note that many of the symptoms are common in those who’ve had certain other viral illnesses, including mononucleosis and cytomegalovirus disease, and that they tend to resolve over time.

“People will recover and will be able to get back to living their regular lives,” said Dr. Catherine Le, co-director of the covid recovery program at Cedars-Sinai. But for the next year or two, she said, “I think we will see people who don’t feel able to go back to the jobs they were doing before.”

Rancho Los Amigos is discussing plans to begin accepting patients who had mild illness and developed post-covid syndrome later, said Lilli Thompson, chief of its rehab therapy division. For now, its main effort is to accommodate all the severe cases being transferred directly from its three public sister hospitals, she said.

The most severely ill patients can have serious neurological, cardiopulmonary and musculoskeletal damage. Most — like Perez — have lost a significant amount of muscle mass. They typically have “post-ICU syndrome,” an assortment of physical, mental and emotional symptoms that can overlap with the symptoms of long covid, making it difficult to tease out how much of their condition is a direct impact of the coronavirus and how much is the more general impact of months in intensive care.

The large, rectangular rehab room where Perez met with his therapists earlier this month is half-gym, half-sitcom set. Part of the space is occupied by weights, video-linked machines that help strengthen hand control and high-tech treadmills, including one that reduces the pull of gravity, enabling patients who are unsteady on their feet to walk without falling. “We tell patients, ‘It’s like walking on the moon,’” Thompson said.

At the other end of the room sits a large-screen TV and a low couch, which helps people practice standing and sitting without undue stress. In a bedroom area, patients relearn to make and unmake their beds. A few feet away, a small office space helps them work on computer and telephone skills they may have lost.

Because Perez was a cook at a hotel restaurant before he fell ill, his occupational therapy involves meal preparation. He stood at the sink, rinsing lettuce, carrots and cucumbers for a salad, then took them over to a table, where he sat down and chopped them with a sharp knife. His knife hand trembled perilously, so occupational therapist Brenda Covarrubias wrapped a weighted band around his wrist to steady him.

“He is working on getting back the skills and endurance he needs for his work, and just for routine daily activities like walking the dogs and walking up steps,” Covarrubias said.

Perez, who immigrated to the U.S. from Guadalajara, Mexico, nearly two decades ago, was upbeat and optimistic, even though his voice was faint and his body still a shell of its former self.

When his speech therapist, Katherine Chan, removed his face mask for some breathing exercises, he pointed to the mustache he’d sprouted recently, cheerfully exclaiming he had trimmed it himself. And, he said, “I can change my clothes now.”

Weeks earlier, Perez had mentioned how much he loved dancing before he got sick. So they made it part of his physical therapy.

“Vicente, are you ready to bailar?” Kevin Mui, a student physical therapist, asked him, as another staff member put on a tune by the Colombian cumbia band La Sonora Dinamita.

Slowly, shakily, Perez rose. He anchored himself in an upright position, then began shuffling his feet from front to back and side to side, hips swaying to the rhythm, his face aglow with the sheer joy of being alive.