Things are looking up for Reds rookie Hunter Greene, just as he envisioned

[ad_1]

Hunter Greene was told not to look up, but he looked up anyway. Up at the third deck. Up toward the nearly sold-out crowd. Up to see what he envisioned since he was just another kid.

Greene hasn’t been just another kid most of his life. The spotlight has trailed him nearly half of his time on Earth. Every pitch studied, every game dissected, every move logged since his fastball first touched 100 mph at Notre Dame High in Sherman Oaks. Landing on the cover of Sports Illustrated, even in 2017, only electrified the hype machine in a sport craving excitement.

And at each stop, at each turn, Greene has oozed a cool confidence. Seemingly never fazed and always ready. So, yes, the 22-year-old pitcher looked up from the mound at Truist Park at 1:50 p.m. Sunday before making his major league debut for the Cincinnati Reds against the Atlanta Braves. He loved the view.

“I looked up right when I got out there,” Greene said. “I wanted to take it all in and enjoy it. I felt really comfortable out there.”

Greene looked it, too, not giving up a hit over the first three innings. Over the next two, he looked like the second-youngest pitcher in Major League Baseball facing the defending World Series champions in his first start, but he didn’t relent. The 6-foot-5 right-hander pushed through five innings, yielding three runs with seven strikeouts to two walks. He threw 92 pitches, 56 for strikes. His fastball reached triple digits 20 times, but he didn’t overthrow.

He exited with a lead the Reds didn’t relinquish to salvage a four-game season-opening series split. His five innings made him the pitcher of record. A win.

His immediate family, most of the small circle in his personal life, traveled from Los Angeles to be there. CC Sabathia, a mentor and probable Hall of Famer, showed up to watch the young Black man expected to continue the tradition of the Black Ace at a time when they’re in short supply.

More friends and family are expected to attend the next time he’s scheduled to take the mound Saturday.

It’ll be a short trip, some 30 miles from where Greene started his well-documented journey. He’ll see something familiar when he looks up. He’ll see a place where his love for the sport was cemented. Where he watched his favorite player, Rafael Furcal, make plays in the hole. The young Black man will see Dodger Stadium on the day after the 75th anniversary of Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier.

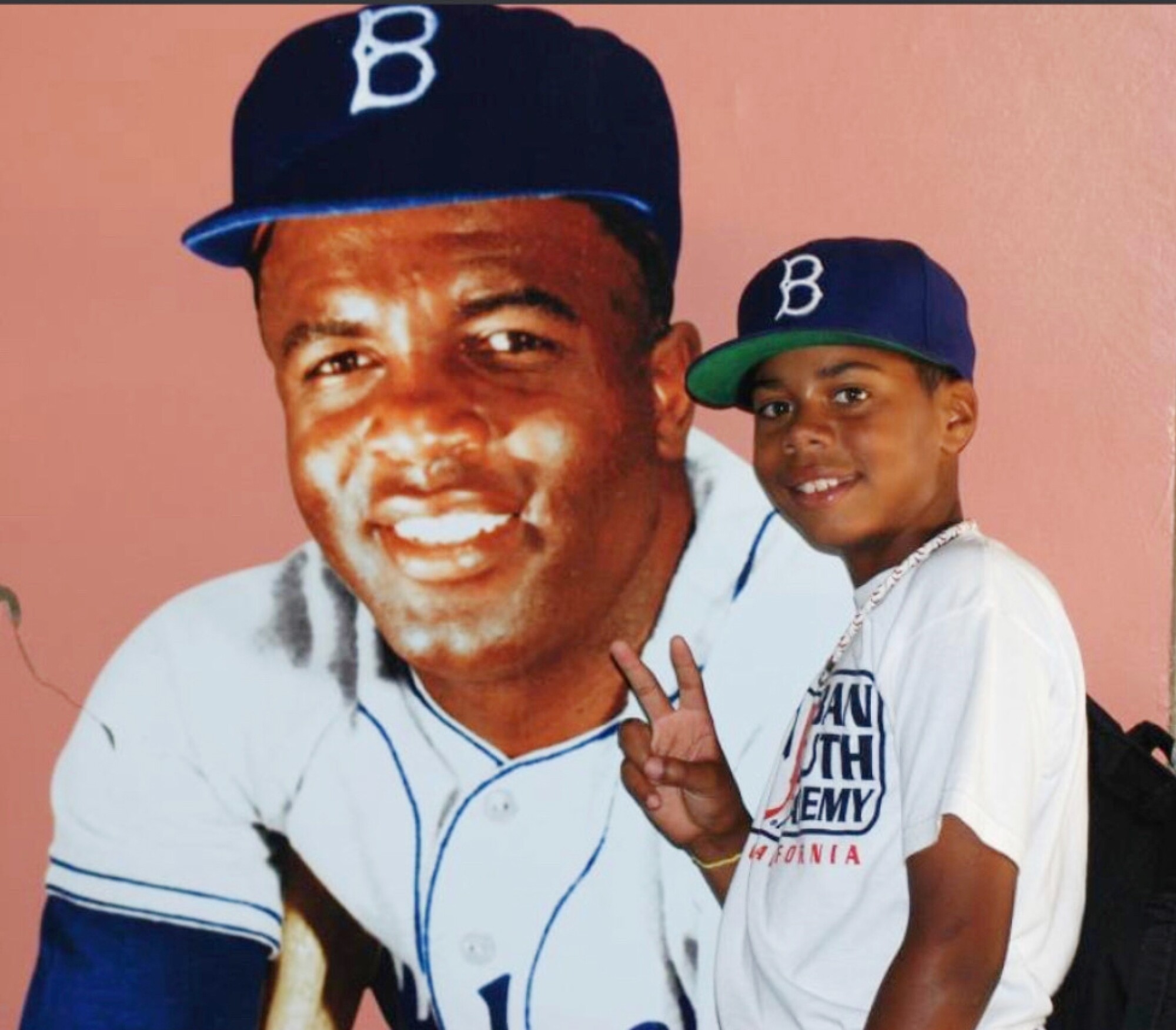

A young Hunter Greene stands in front of a photo of Dodgers legend Jackie Robinson.

(Russell Greene)

“It’s going to be fun, man,” Greene said. “It’s a beautiful stadium. I’m sure it’s going to be packed. But I’m looking to dominate and go right after these guys and compete and have fun.”

*******

Russell Greene recognized his son was different early. The proud father, a prominent private investigator who worked for renowned attorney Johnnie Cochran, keeps a photo that crystalizes the realization. In it, the father and his 4-year-old son are kneeling next to each other. Both are leaning on a bat. Hunter’s is plastic and black. He’s wearing a black helmet. Hunter’s hand-eye coordination, he recalls, was abnormal.

“And I knew then,” Russell said.

A decade later, Hunter committed to UCLA before playing in a high school game. By 14, he was throwing 93 mph. The next year, he was named the C

alifornia player of the year and made the under-18 U.S. national team. When he wasn’t on the mound, he was one of the best shortstops in the country. People packed ballparks to gawk. The national attention followed.

“We had fans trying to get their Sports Illustrated magazine signed by him while we’re trying to get on the bus,” Notre Dame coach Tom Dill said. “We had lines of people. I had to stop it. I even saw some opposing coaches in the line.”

That UCLA commitment became a backup plan by draft day in 2017. The Reds selected him No. 2 overall and gave him a $7.23-million signing bonus — the largest windfall since constraints on draft spending were first implemented in 2012.

Greene was viewed as a first-round pick as a shortstop and began his professional playing both ways, as a pitcher and designated hitter, in rookie ball that summer. But the Reds had him focus on pitching starting that offseason. The plan was for him to plow through the minors and make his major league debut at 20. That didn’t happen.

Hunter Greene, right, talks to Commissioner Rob Manfred after being selected No. 2 overall by the Cincinnati Reds in the Major League Baseball draft on June 12, 2017, in Secaucus, N.J.

(Julio Cortez / Associated Press)

A year after being drafted, Greene gave up a two-run home run in the Futures Game at Nationals Park but dazzled with 19 fastballs over 100 mph, topping out at 103.1 mph, in 1 1/3 innings. He was 18 years old. The hype persisted. Two weeks later, his rise abruptly stalled. He was diagnosed with a torn ulnar collateral ligament — the precursor to Tommy John surgery. Greene and the Reds unsuccessfully tried rehabilitating the injury without the operation. In April, he went under the knife.

“I remember the media attention was as if he had died in a plane crash,” Russell said. “I mean, the news spread like you wouldn’t believe. That can do a lot to a person.”

The COVID-19 pandemic shut down the 2020 minor league season so Greene didn’t pitch in an official game for two years. There were moments of doubt and frustration away from the competition. But he said those 24 months provided lessons.

“I learned a lot about myself, about other people, people that I thought had my back that really didn’t,” Greene said. “Just because I wasn’t playing, so, if you’re not playing, some people will kick you to the curb a little bit. I learned a lot about some folks and people in my circle that I thought were in my circle that really weren’t.”

With the injury, the attention dissipated. For the first time since middle school, Greene wasn’t under the microscope. The setback presented challenges. But there was a sense of liberation rehabbing in anonymity, throwing on backfields, working to improve.

“For most of my career, it’s been hard for me to feel like I can get my work in without feeling like every time I step on the field it’s got to be the best of the best,” Greene said. “I got to strike everybody out. I got to look perfect. While other guys don’t have that spotlight so they’re able to develop naturally without any of the extra stuff. You can fail without it being on a freaking national platform.”

Hunter Greene pitches during the Futures Game at Nationals Park on July 15, 2018, in Washington.

(Rob Carr / Getty Images)

“For most of my career, it’s been hard for me to feel like I can get my work in without feeling like every time I step on the field it’s got to be the best of the best”

— Cincinnati Reds pitcher Hunter Greene

He felt like himself again by the third bullpen session of his throwing program and returned in 2021 arguably better. He began last season with double-A Dayton and dominated. He totaled 60 strikeouts to 14 walks and a 1.98 earned-run average in 41 innings in seven starts.

By mid-June, he was pitching for triple-A Louisville. In August, he touched 105 mph. In one outing, he threw 37 pitches of at least 100 mph, setting the record across all levels since pitch tracking data began in 2007. He finished with a 4.13 ERA and 79 strikeouts in 65 1/3 innings on the majors’ doorstep. The hype was back.

“I don’t consider his ability to throw over 100 miles an hour a curse,” Russell said. “Some people might see it as a curse because it’s a curse to injury. But I’ll tell you what, that 100 mile-an-hour fastball made him a significant amount of money that’s been well-invested that Hunter won’t have to work a day in his life. And how many people can say that?”

******

In 2007, Russell started bringing a 7-year-old Hunter to Major League Baseball’s first Urban Youth Academy in Compton. They would drive the hour each way from suburban Stevenson Ranch three times a week to the academy in the inner city where MLB was attempting to popularize baseball among Black youth.

Why? Russell said there were racial incidents and favoritism working against his son at the local league. Hunter wasn’t given a chance to pitch or play shortstop. He played only third base for three or four innings and was benched for the rest of the game. So, after hearing about the academy from a friend, Russell enrolled his son.

“He was discouraged not seeing anyone who looked like him, on top of coaches screwing with him,” Russell said. “I saw that, and I didn’t want him to get away from the game. I wanted him to see other players like him, that struggled and succeeded all at the same time. The academy was such a beautiful place.”

Greene quickly felt at home. He was allowed to play shortstop and pitch. Practices were fun working with retired major leaguers, including former Dodger Ken Landreaux. Darrell Miller, the academy’s director and a former Angel, recalled Greene addressing a crowd at a fundraiser.

“We had to build a little stand for him, and he brought the house down,” Miller said. “One of the most incredible speeches. I told him, ‘Hunter, you’re going to influence the world in some way, shape or form.’ You could see greatness in him as a 7-year-old.”

Greene later wore Robinson’s No. 42 and won an essay contest created by Robinson’s daughter, Sharon, when he was 13. He wrote about persistence and staying focused while his younger sister, Libriti, went through treatment for leukemia.

He has held youth baseball camps in Inglewood since turning professional. He has staged baseball clinics and given out turkeys in Compton. He wasn’t raised in those predominately Black communities, but he has been drawn there to help.

Notre Dame High baseball player, Hunter Greene.

(Los Angeles Times)

“Seeing guys that would come up like me or be able to inspire that next generation was really important,” Greene said. “So every time I step on that mound, that’s my focus and being able to put on for the next generation and African American players is always special.”

******

Greene reported to spring training — after working out with veterans Sonny Gray and Marcus Stroman — certain he would reach the majors in 2022. The question was when.

Reds pitching coach Derek Johnson said Greene was a “tweener” when the club first assembled in Arizona. The door burst open days later when the club traded Gray to the Minnesota Twins. Greene made three appearances in the Cactus League. In the third, he gave up seven runs, five earned, over two innings against the Chicago White Sox. The criticism resurfaced.

“It was like the sky is falling,” Russell said. “I got a lot of calls with, ‘What’s wrong with Hunter?’ Well, nothing’s wrong with Hunter. It’s like can he work on some other pitches? He’s got to be able to sharpen his tools without all the scrutiny.”

The Reds, entrenched in rebuilding mode, did not deviate from their plan. Greene, the organization’s top-ranked prospect, broke camp on the opening day roster. He is one of three rookies in their rotation, marking a new era for a franchise without a playoff win since 2012.

“I think his off-speed stuff has gotten better in the last couple of years,” Johnson said. “And really now, the next step is, ‘OK, what do I do against a left-handed hitter? What do I do against a right-handed hitter?’ Putting all his stuff together and making it fit, making it work for him.”

The first pitch of Greene’s big league career was a 98.3 mph four-seam fastball — a pitch talent evaluators believe can be too flat too often — to Eddie Rosario for a called strike over the inside corner. His fourth was a 100.1 mph fastball Rosario rolled over for a ground out.

“Seeing guys that would come up like me or be able to inspire that next generation was really important”

— Cincinnati Reds pitcher Hunter Greene

Cincinnati Reds pitcher Hunter Greene, right, is greeted by teammates after completing the fifth inning against the Atlanta Braves on Sunday.

(John Bazemore / Associated Press)

He challenged the next batter, All-Star first baseman Matt Olson, with a 100.3-mph fastball on a full count. Olson whiffed. Career strikeout No. 1. Next, Austin Riley, a Silver Slugger winner in 2021, didn’t stand a chance. Slider for a called strike. A strike swinging at a 99.5-mph fastball. An 87-mph slider off the plate, sharp enough to produce a bad swing from Riley. Three pitches, three strikes, and a third out. Greene’s first inning was in the books.

He surrendered a run in the fourth inning but escaped a bases-loaded, one-out jam with a diving catch from first baseman Joey Votto. There was more turbulence in the fifth. Travis d’Arnaud jumped on a first-pitch 99-mph fastball to slug a home run. With two outs, Olson launched Greene’s 86th pitch, a 101-mph fastball over the wall in center field.

Reds manager David Bell contemplated pulling the rookie. He hadn’t thrown that many pitches since last season. But Bell let Greene face Riley a third time. He coaxed a flyout to end the inning and his outing.

“He couldn’t have handled today any better than he did,” Bell said.

Greene admitted to battling fatigue. Building the stamina to pitch deeper into games will come with maturation. The goal in 2022, above all, is to stay heathy. He anticipates struggles. So does his father. That young man with the 105-mph fastball, Russell says, is still developing. There will be rough patches. Sunday in Atlanta, an afternoon they all imagined, wasn’t one of them.

“It was nothing short of spectacular,” Russell said. “A million butterflies in one stomach.”

On Saturday, a deeper contingent of friends and family will head to Dodger Stadium to watch him pitch. It has been both a short and long road to this point, to making this start in his backyard on this particular weekend. The view will be nice.

[ad_2]

Source link